A useful quote to look at for next essay re post modernism and the loss of reality.

https://ocasjf.wordpress.com/2018/02/07/assignment-5-ideas-notes-reflections/

SJField – OCA Level Three Study Blog

Body of Work & Contextual Studies

A useful quote to look at for next essay re post modernism and the loss of reality.

https://ocasjf.wordpress.com/2018/02/07/assignment-5-ideas-notes-reflections/

While doing UVC in 2016, I was asked to look at Rhetoric of the Image and talk about a couple of advertisements, relating them to Barthes’ ideas. It’s really interesting to look back, as the examples I explored were to do with the yet-to-be-held referendum. Barthes’ style is so opaque at times, I am still not sure if I was making the right sort of connections, but I don’t think I’d change much of what I said as I view my blog in retrospect, with three years of history between the time I wrote it and today.

Some notes of my most recent reading of Rhetoric of the Image:

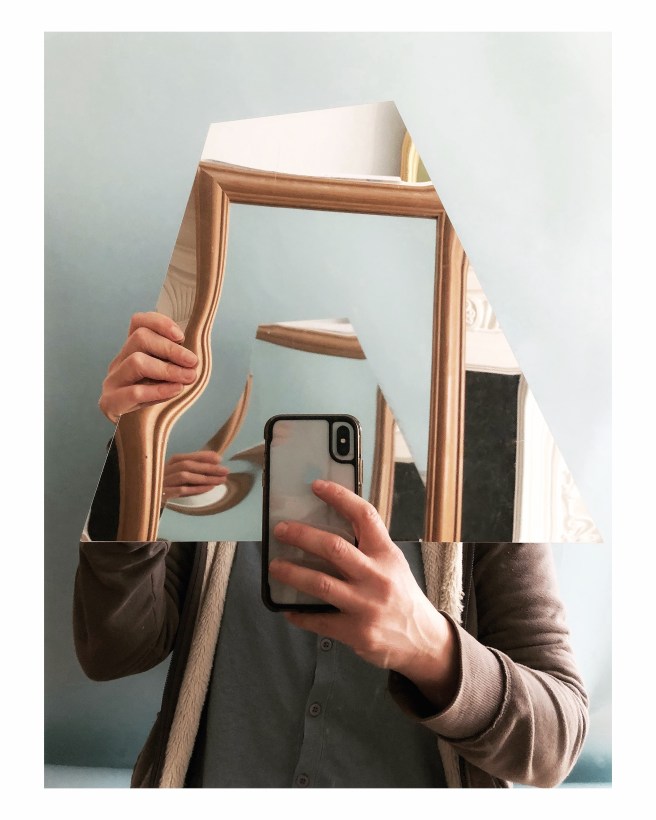

The Linguistic message

These adverts (regardless of one’s thoughts about the content) are tapping into society’s mistrust of advertising and consequently meaning. As the meaning of advertising signification is now suspected of being false, (and so much more besides) we might question Barthes statement in retrospect. Although unusual, these adverts do not subscribe to Barthes analysis so easily. Meaninglessness is a big issue today – also referred to as ‘fake news’. A century of being manipulated by advertisers might be responsible for this sense of society having been gas-lit, leaving us all in an unstable landscape (like the cartoon landscape of Holden’s film). Images, which can and do invite multiple readings, even with the tyranny of advertising slogans, but which ultimately lie to us have contributed to this.

(Below – my comments are in orange, otherwise quoted from Barthes)

The Denoted Image

Refs: All accessed 23/24 June 2019

https://stylecaster.com/beauty/vintage-chanel-no-5-ads/#slide-11

http://www.cinemamuseum.org.uk/2019/andy-holden-laws-of-motion-in-a-cartoon-landscape/

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/may/25/eu-referendum-poster-minority-ethnic-voters

Barthes. R (2013) Rhetoric of the Image in Visual Culture: A Reader, London, Open University, Sage Publications; 33-40

Flusser, V. (2000) Towards a Philosophy of PhotographyTrans. Mathews A. (Kindle Edition) London: Reacktion Books

N. K. Hayles. (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

As with the previous post, I first looked at this during UVC. It is a less hefty, daunting article than Benjamin’s and therefore more digestible. My first encounter seems to have been about becoming familiar with information; names, concepts, era-specific concerns.

Notes:

https://www.academia.edu/5728395/The_Photographic_Activity_of_Postmodernism

Wrangham, R. 2019 The Goodness Paradox (Kindle Edition), Profile Books

I am so glad I did Understanding Visual Culture earlier in my OCA studies – much of what we’ve been asked to look at in the early stages of CS was covered in the previous version of UVC. Saying that, the introductory passages in the CS folder are well written and give excellent and brief but precise descriptions of the main ‘ism’s, which I found useful.

I note the importance of context and meaning in Post-structuralism and see how it echoes a developing understanding of context within interdisciplinary conversations across the sciences, and in particular within physics. I think one of the first times I came across this idea about context and particles may in Carlo Rovello’s Reality is Not What it Seems (2017), although Hayles must surely have mentioned it in How We Became Post Human (1999) which I read earlier. But I have since seen it discussed in a number of other books, including The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision (2014) by Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi who do an excellent job of linking up various disciplines in a way that some other less expansive thinkers don’t. (Perhaps I mean to say other myopic and parochial thinkers, but I’m being polite.)

Rovelli writes, “The theory [quantum] does not describe things as they are; it describes how things occur and how they interact with each other. It doesn’t describe where there is a particle but how the particle shows itself to others. The world of existent things is reduced to a realm of possible interactions. Reality is reduced to interaction. Reality is reduced to relation.”

and

“In the world described by quantum mechanics there is no reality except in the relations between physical systems.” (Rovelli, 2017; 115)

This is crucial because that theory informed the way code was developed. Although language might be considered a metaphysical system, we everyday users of code (a form most of us have little knowledge of) internalise its mechanisms, which, it is argued, inadvertently influences our understanding of reality. This is further reinforced by systemic feedback loops. Perhaps it will become important to try to describe what I mean by this elsewhere or later in the module. I can see feedback being something worth playing with for BOW at some point, and fun too.

We have been asked to read the following essays/extracts and I think it will be interesting to see what I make of them in comparison to how I responded before. I am not going to read my earlier notes yet, but am placing them here to return to later after I’ve read the articles.

Brief of notes on The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism

We are also asked to look at Crimp’s Museum in Ruins and I made some work which I felt was a response to what I’d read there shortly beforehand.

A5: A Sketch, putting myself in Michael Snow’s Slidelength (1971)…the year I was born, incidentally

Another UVC post worth relooking at are my thoughts stemming from Chandler’s Semiotics: The Basics:

Finally, although many writers connect digital technology to photography, few make the connection with quantum theory (which underpins part of digital development in many ways). However, Fred Ritchin does in his book, After Photography (2009). The other is Katherine Hayles in How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (2009).

Ref:

Rovelli, C. 2017 Reality is Not What it Seems London Penguin