We are asked to look at Chapter 2 “Photography” by Richard Howells (2011). To begin with, the chapter sums up the very short history of photography. Although not Areilla Azoulay’s non-Cartesian version, which I talked about in my DI&C essay, and which posits that we cannot separate the invention of photography from its related activities, that of empire building which began in the 14th century when Columbus sailed across the Atlantic and began the process of taking people and land on behalf of European conquerors. I’ll touch on this briefly later. However, the author does take us back to cave-drawing (as far back as 25 000 years rather than 40 000 which is where academics have placed the earliest discoveries; coded symbols that can found over eons of space and time). This is important because photography is simply one more way for us to exteriorise our inner selves, to other the self, to store consciousness. That it’s mechanical is important but doesn’t render it less than.

It was interesting to touch base with the received story again, having read about it in various books while studying but specifically, in a wonderfully entertaining book called Capturing the Light by Helen Rappaport and Roger Watson (2013) which goes into much greater detail, although with less critical depth.

However, I found it difficult after reading the chapter to get beyond the inclusion of Roger Scruton’s essay, Photography and Representation‘ in “The Aesthetic Understanding‘, Essays in the Philosophy of Art and Culture‘ (1983). Scruton isn’t only a Conservative, he is a reactionary extremist who promotes the most appalling ideas and is a friend of the Spiked bunch, who, quite frankly, seem completely nuts. (And I used to quite like some of what Frank Ferudi said about parenting.) Scruton was recently sacked from his position at the head of the Government funded Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission (what he was doing there, is anybody’s guess – a mate of a mate, no doubt) for making comments that aren’t even worth repeating. He has spent his whole life offending people and seems to feel hard done by, having ostracised himself from various British academic institutions. His own father was, by all accounts, chaotic and damaged and very anti-establishment. Read into that what you will.

I appreciate that the original chapter was written some time ago (2003) and Scruton may, in keeping with the times and contemporary discourse, have virulently amplified his conservative message in recent years. But I find his argument sort of ridiculous – and Howell talks about it being flawed. I also know difference of opinion is important and having both sides of any argument is thought to bring about some form of synthesis, leading to a balanced idea of reality. However, modern science and philosophy are rendering the arguments included in Howell’s chapter and in particular Scruton’s, not only flawed but almost irrelevant. Before introducing Scruton, Howell tells us how some people felt that photography cannot be art because it merely records the natural world, reality, as it is, which is where Scruton we are told, positions himself.

For a moment, I’ll deviate here and talk a bit about ‘reality’.

Two years or so ago I got off a train at a station beyond my intended stop. I realised my mistake but wasn’t sure how long I’d been distracted by my book, and looked at the map on the platform to see where I was and where I needed to get to. For a short moment, but long enough to cause a sense of panic and alarm, my memory stopped working. I recognised the signs on the maps as signs but had no recollection of what any of them meant, no access to their meaning. It was like looking at a map in a foreign language at the same time as not even knowing what a language might be. It may have been an early sign of something sinister healthwise to come, however, it has not happened since and I hope and suspect it was simply a brain glitch brought about by stress, tiredness, and distraction. It felt like it lasted about a minute. The experience, however, demonstrated what my consciousness and its integral function, memory, does for me. It enables me to get from A to B so I can survive. Without that ability I would not be able to move about in the world, feeding myself, interacting with people, finding a mate – doing all the things that keep the genes alive and reproducing. This is what our consciousness is – an evolved survival mechanism. And as hard as it is to accept, we have evolved to see only what we need to see in order to exist. We have a limited, locally based view of reality that is myopic but highly specialised. Some criticise this materialist view suggesting it leads to emptiness, an existence that lacks meaning, but the illusion of reality is literally all we have and to belittle or undervalue it isn’t automatic or necessary. One hopes we can afford to be honest with ourselves, although as we look about today, it does at times seem perilous and perhaps terrifying for people.

I am looking forward to receiving my delayed copy of “The Case Against Reality” by Donald D Hoffman. But since 2015 I have been reading as much as I can to understand this illusion of reality including Reality is Not What is Seems Rovelli (2016), The Ego Trick Baggini (2015), and The Biological Mind Jasonoff (2018) amongst many others which look at life systemically. I think the science contained in these books potentially nullifies any arguments about photography being simply a recording of reality – because our reality is SO subjective and particularly nowadays when digital technology is fundamentally changing what we expect from reality – and because any language form, photography included, is an emergent property which is what is so fascinating about mark making – however we choose to do it. And that’s before we even touch on individual subjectivity (as opposed to species subjectivity), technical ability, and choice, or processing whether in the darkroom or your desktop.

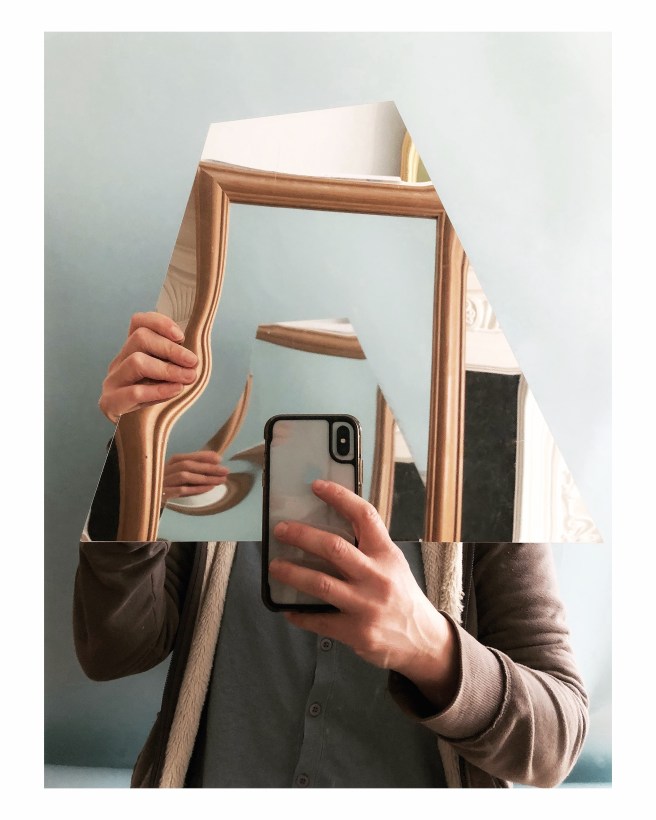

And in any case, the arguments against photography of any description being an art form because it is a copy, where photographers simply record rather than dictate what’s included, were made redundant the moment a urinal was placed in an art gallery. If you think photographs merely copy reality, then they are the ultimate readymade. Although I do see some conservatives are likely to dismiss appropriation as a viable art form too, missing the point of it entirely. But like the evolving nature of gods and God as civilisation develops, what we need from art changes too. And conceptualism rather than dogmatic religious iconography is clearly more relevant today as the nature of reality is unpicked and newly understood. Photography, being an emergent property that came along with the evolution of technology over several centuries alongside its sibling, or perhaps its close cousin, Capitalism, is not only interesting as a concept but crucial to the way we see and understand life today, and therefore an integral form in any artistic exploration regardless of whether it ‘ideal or real’ (Scruton’s distinctions). Even if all the artist is doing is making something pretty, which is of course just as valid as documenting society, or commenting on language. These distinctions are as silly as the ones about digital technology not being ‘lovely’ enough to produce art.

I am looking forward to receiving my book by Hoffman so I can keep investigating this subject and bringing it into my own work. In the meantime, I used to think that all the technological advances we relied on were changing our evolutionary path whereas now I see that they are part and parcel of our evolutionary path. They are expressions which lead to feedback loops. I think that’s why distinguishing between forms and saying one is art and one isn’t is a limited and limiting view.